---------------------------------------

A deep well of discontentDAVID EBNER,

From Saturday's Globe and Mail

October 12, 2007 at 11:57 PM EDT

CALGARY — When

Ed Stelmach unexpectedly became Premier of Alberta last December, following the long reign of Ralph Klein, a quiet but important shift occurred: Power moved from Mr. Klein's home base in the energy capital of Calgary to Mr. Stelmach's traditional territory, rural Alberta.

Mr. Stelmach has hardscrabble roots on a farm near Edmonton that his grandfather settled in 1898 and in his early 20s he returned to work the homestead instead of heading to law school after an older brother died unexpectedly. That turn back to the farm led him away from corporate power, and even though Mr. Stelmach put grander ambitions on hold, he slowly and surely still managed to rise to the province's highest office, arriving there without years of hanging out at

Calgary's Petroleum Club, unlike Mr. Klein and other predecessors.

Today, Mr. Stelmach is poised to make the most important economic decision in the country this year – promising a decision by month's end on what's fair for energy royalties. He is not an eloquent man but is known as a careful leader, a listener – precisely the opposite of Mr. Klein, a shoot-first-ask-questions-later man whom oil executives considered a trustworthy buddy.

Now, the blunt question is whether Mr. Stelmach has the acumen to make the right decision on royalties, and business fears what it calls a potential catastrophe if he makes the wrong move and sinks the country's most robust economy. Billions of dollars, at the very least, are on the line, along with thousands of jobs – in Alberta and across Canada. Mr. Stelmach's government is not particularly popular and there is a strong temptation to play the populist card given the polling numbers that show some support for a landmark report that calls for significantly higher royalties to be implemented in full.

No wonder: The price of oil yesterday rose past $84 (U.S.) a barrel, a record.

Sensing an opportunity for electoral success – the last vote was in November, 2004 – Mr. Stelmach is pondering a snap election this fall if his decision on royalties goes over well. The pressure, with energy companies threatening to pull at least $3-billion (Canadian) out of the province next year, is immense. Where Mr. Stelmach stands is unclear: The farmer has been criticized this month for being too close to industry and possibly cracking under pressure from it.

A spokesman for Mr. Stelmach said yesterday no decisions have been made – the situation is “fluid” – but added: “The status quo is not an option.”

“I think Stelmach's going to make the right decision,” said George Gosbee, chairman of

Tristone Capital Inc., a Calgary investment bank that has worked to broker a balance between higher royalties and keeping the province's economic engine running. “It's going to be a big win, for all Albertans.”

The debate shines a light on a maturing Alberta that this year has blossomed beyond the energy monolith many Canadians take it for. Politically, even though the Conservatives have ruled for almost four decades, the public discourse is suddenly far more lively and diverse. Dissent is no longer a synonym for treason.

It is a marked turn away from the era of Ralph Klein's reverence for big business and a re-emergence of the more collective spirit of the 1970s, when then-premier Peter Lougheed launched the Conservative dynasty with a political style that was far more centrist than right wing. The royalty report itself – which was written by a panel that included three economists, a retired forestry executive, a retired oil executive and a technology entrepreneur – was not a staid government tome. It was written for a wide audience and had an almost activist tone, starting with its title:

“Our Fair Share.”“[The royalty report] has tapped into a pocket of malcontent that nobody knew existed,” said David Yager, chief executive officer of

HSE Integrated Ltd., a small energy services company, and a columnist for Oilweek magazine. “But when you're premier, you can't take advantage of the province's most important industry for short-term political gain. There are opportunities to take a little more but what I found discouraging was the tone of the report.”

Much of the debate has been vitriolic, with panel members facing accusations of being “uneducated” in the practical business of oil and gas and having “grossly underestimated” key data regarding industry costs. Mr. Yager said “rage” was the predominant emotion, following the initial “shock.” Foreign investors made specious declarations comparing Alberta with Venezuela, with

Deutsche Bank Securities Ltd. suggesting there was some sort of socialist revolution under way as it entitled a note to investors: “The Bolivarian Republic of Alberta.” The respected market analyst

Don Coxe yesterday referred to it as a “Putinesque abrogation” of the tradition of royalties.

But lost in the shrill and deeply emotional debate are the numerous nuances of a quickly changing business in the province. When the public review began in April to determine whether Alberta was getting a fair share of energy money, all eyes were on the oil sands, where all facts pointed to the obvious conclusion of higher royalties.

In the northern hinterlands of the province lies a huge expanse of boreal forest and the oil sands, billed as the second-biggest reserve of oil on the planet. For decades, the very low-grade resource was considered barely useful until high oil prices, technology and a generous royalty regime ignited a fever, bringing tens of billions of dollars in capital flowing through Calgary and Edmonton to Fort McMurray in a mad building boom.

A decade from now, conventional oil and gas production — and royalties from those sources — will no longer form the foundation of Alberta's treasury, and the province is depending on oil sands to make up the difference, as production in the region is projected to roughly triple over the next decade. Without this, Alberta could actually slowly skid towards the have-not provincial status it held before the discovery of a giant field of conventional oil near Edmonton in 1947.

When the six-member review panel came out with its report on Sept. 18, the surprise was not that it called for higher rates in the oil sands but that the main target for immediate increases was aimed squarely at the struggling natural gas business.

The critical and most controversial issue – natural gas – has underpinned Alberta's economic success and its overflowing treasury. The so-called Calgary oil patch is in fact a gas capital, with a shift only now beginning to swing to the oil sands.

Canadian Natural Resources Ltd.(TSX:CNQ), the country's second-largest producer, is the embodiment of this evolution, beginning life in the deep recession of the late 1980s as a scrappy gas producer and growing into a giant gas producer – and now making a big, long-term bet on the oil sands.

But the oil sands remains a tomorrow story, a key source of the province's long-term revenues.

Today, Canadian Natural – and the province – depends on natural gas. There are more than 100,000 producing wells in Alberta, but it's only a very small number that really count, those that dot the rugged Foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Mr. Stelmach's decision this month is absolutely crucial for corporate decisions on winter drilling in those Foothills – the short window lasting a couple of months, when the ground is frozen, to move rigs in and out to hunt for the few remaining big gas targets buried thousands of metres below the surface.

According to Tristone, which has worked closely with Alberta civil servants in Edmonton to produce new work it will present on Monday, these are the 5 per cent of Alberta's gas wells that generate 50 per cent of the province's gas production and provide 63 per cent of gas royalties – which in turn accounts for roughly 40 per cent of all royalties currently collected by the province.

The royalty review panel felt the province wasn't getting its fair share from these big wells, which spit out piles of cash at high prices but also cost millions of dollars to drill (and successful drilling is far from assured). The panel said its recommendations would in fact see royalties on about 80 per cent of gas wells reduced at recent gas prices, aiming to encourage continued production of modest wells – but, stepping back, those tiny wells are a secondary concern in the bigger picture.

Under the recommendations, the prolific gas wells in the Foothills – those that uncover major reserves to heat homes across the country – would see their value slashed to 59 cents per million cubic feet from 98 cents, according to Tristone, as government takes much more money up front.

Pedro van Meurs

Pedro van Meurs, a respected international consultant on royalties upon whom the panel relied heavily, indicated in a July report that Alberta had “considerable competitive scope” to get more when gas (or oil) prices are high. But he added that deep wells in the Foothills generally require high initial output to justify drilling them, suggesting that taking more up front “may not deal effectively with deep gas wells” and recommended further investigation of incentive programs to encourage such drilling.

One panel member, speaking off the record yesterday, said if there is good evidence, the government should consider the balance between gas royalties on such wells and economic development. “That's their job,” the person said. “There could be room to move there.”

At current natural gas prices, with the panel recommendations, drilling in the Foothills makes no economic sense, according to Canadian Natural and all other leading explorers in the region. It is why Canadian Natural said it would slash spending by $800-million next year if the recommendations are fully adopted; it's why

EnCana Corp. (TSX:ECA) announced its intention to take $1-billion off the table; it's why

Talisman Energy Inc. (TSX:TML) is mulling a $500-million cut and

ConocoPhillips Co. (TSX:COP) plans to withdraw another $500-million.

The royalty panel envisioned its recommendations quickly adding $2-billion to the provincial treasury, with half of that coming in more money from gas; the potential cuts announced to date already exceed the projected gain.

And if all these wells don't get drilled this winter – beyond the job losses in the field, from the rigs to all the small towns like Edson that support the business – the province's natural gas production will go into freefall. This is already partly in motion, as the

National Energy Board this week predicted in a report that showed a possible a decline of 15 per cent in Canadian gas supplies by 2009 because of relatively low prices.

With gas output sliding, the government's royalty take is headed down, not up.

Still, don't cry for the poor natural gas explorer: They are playing a game of big risk and big reward – and the rewards can be fantastic. Natural gas fuelled EnCana's $6.4-billion profit last year, the biggest in Canadian history, not to mention Talisman's $2-billion take, its best ever, and Canadian Natural's $2.5-billion, also the most the company has ever made.

Because Ralph Klein capped gas royalties in the early 1990s at very low levels, wells in the Foothills can produce excellent rates of return of more than 15 per cent at higher prices, such as $9 per thousand cubic feet. The panel's recommendation would cut that to 6.5 per cent, Tristone calculates.

In between is the balance Mr. Stelmach must strike – and executives are ready to deal.

“There's room at higher prices. It's just at what prices that kicks in,” Steve Laut, Canadian Natural president, said in an interview. “By increasing the take, the [review] panel changed how it's collected. The take has shifted to the front end. The government gets their share sooner and that, obviously as a company investing the capital, means we get our returns later. As economics work, it drives the returns down dramatically. And by doing that, they've effectively made large portions of the Alberta basin uneconomic.”

Canadian Natural this week issued the most detailed assessment of what the royalty proposals mean to its business, warning of job losses for 4,000 contractors as it slashes the number of gas wells it might drill in 2008 to just 88 from 253 this year.

“The people that will take the brunt of this royalty proposal will be the people in the field. The guys on the rigs, the pipefitters and welders in the [fabrication] shops in Edmonton, the guys driving the truck, the pipeline crews, the small business person that just bought two new trucks to haul equipment. They will take the brunt.”

Just yesterday,

Mullen Group Income Fund (TSX:MTL.UN), a small energy services firm, said it is handing temporary layoff notices to as many as 100 people because of low gas prices and royalties uncertainty.

For Mr. Stelmach, whose core support is in rural Alberta, this is an important part of his balancing act. A poll this month found that almost nine out of 10 Albertans agreed the province isn't getting its “fair share” from oil and gas and two-thirds wanted to see the royalty recommendations adopted in full rather than in part.

“The royalty report has raised the expectations of Albertans tremendously,” said Geoffrey Hale, a political scientist at the University of Lethbridge.

Beyond the headlines were nuanced revelations. About 55 per cent of Albertans want to see higher royalties in the oil sands but roughly the same number believe royalties charged on conventional oil and natural gas wells should stay the same or be cut, which was precisely the sentiment in the air when the public royalty review quietly began in April in an almost empty hotel conference room in Grande Prairie, the hub of 50,000 residents in northwestern Alberta that depends on gas drilling.

Going beyond natural gas – where the price of the commodity is down roughly 20 per cent from a year ago – is the world of oil, where the spotlight shines far brighter and many more people know that riches are being made, given that the price of crude sits at more than $80 (U.S.) a barrel. The panel also called for higher royalties on conventional oil production, which had been capped at about $40 a barrel – leading to an unfair amount of profit going to corporations rather than citizens, who are the owners of the resource, while firms lease the rights to explore and produce.

While corporate Calgary has angrily reacted to the royalty review recommendations, more nuances are revealed in who is standing up and what they are saying – and companies that are quietly not speaking out at all.

Suncor Energy Inc. (TSX:SU), the oldest and second-largest oil sands miner, has not made any public declarations and its stock remains near an all-time high of about $100 (Canadian) a share, just a bit below where it was before the royalty report.

Marcel Coutu, chief executive officer of

Canadian Oil Sands Trust (TSX:COS.UN), which holds the biggest stake in the biggest oil sands miner Syncrude Canada Ltd., told The Globe and Mail after the report that there is room for “some form of compromise,” saying: “A burden must be chosen that will optimize the eventual value of this resource.”

Canadian Natural, which is investing $7.6-billion to build an oil sands mine, said it will forge ahead regardless and plans to develop two more phases of its Horizon mine, costing billions more.

Don't be mistaken: The energy companies aren't content with all the royalty ideas for the oil sands. In the 1990s, before the boom, a very generous royalty regime was put in place to encourage development, with a rate of just 1 per cent of gross revenues until a project recouped its capital costs, plus a return similar to a government bond, before the rate jumped to 25 per cent of net revenues, taking out many operating costs before paying the government.

The panel proposed the 25-per-cent rate rise to 33 per cent, which hasn't really been debated, but industry is quite critical of a proposed severance tax to be charged from the first day of production if oil prices are higher than $40 (U.S.) a barrel, a level now considered to be quite low.

This tax, oil companies argue, is punitive to projects that don't mine the oil sands and instead recover it by drilling wells and injecting steam to draw it to the surface. This technique and future variations thereof will be used to recover most of the resource bitumen in the oil sands; mining scrapes off just a fraction of the available bitumen from the surface.

Petro-Canada (TSX:PCZ), which is working on a $14.1-billion (Canadian) mine, didn't complain about higher royalties but said the severance tax means steam injection projects can only work at $100 a barrel. The company said it believed a compromise could be worked out. Canadian Natural said $7-billion of steam-injection projects on the drawing board would have to be shelved. EnCana, which is a steam-injection pioneer, said its existing projects will work but the severance tax puts billions of dollars of future plans in jeopardy.

Like increasing the royalties on deep gas, the tax is criticized for taking too much too soon from multibillion-dollar projects that take years to develop.

But again, unlike earlier this year when oil companies weren't willing to compromise on anything, Tristone suggested a tax that started kicking in at $70 a barrel after a project recovers its capital costs and an increase of the initial nominal royalty rate of 1 per cent to 3 per cent on gross revenues – which would last through an oil sands project's entire life, rather than just the early years. On the 25-per-cent figure, Tristone said it should stay static, saying its plan would get more for the province than the panel's proposals.

Tristone's Mr. Gosbee said his firm's idea of compromise caused private grumbles among Calgary's top executives – but given that the debate has shifted radically from where it stood before the royalty report, the willingness to accept a pragmatic solution has caught on under the threat of something worse. Like comedian Larry David has joked, a successful compromise is when everyone's unhappy.

For Mr. Stelmach, in a job where he is supposed to keep as many people as happy as possible, the challenge is considerable. He is no stranger to struggle but now must deal with the greatest challenge of his life, to be made under the threat of an economic slowdown or worse, and try to shake off an image of economic ineptitude.

The government is completing a technical review of the royalty report and has met privately with a constant stream of industry representatives. This coming week Mr. Stelmach begins to draft his decision and craft his political message. On Oct. 24, he is slated to appear on television to explain at least some of his thinking to Albertans – with a full decision promised by Halloween.

Then, if it goes well, Mr. Stelmach calls an election, to seek a mandate to validate his decision and leadership after almost a year as premier, in a job to which he ascended only by a vote of Conservative Party members.

Keith Brownsey, a political scientist Calgary's Mount Royal College, said Mr. Stelmach has the opportunity to hit the delicate balance between Alberta as a whole and industry.

“Some concessions can certainly be made to the oil and gas industry without appearing to cave to their demands,” Mr. Brownsey said.

“For an election, he could wait until next spring but my inclination would be to strike while the iron is hot, hold up the royalty decision and declare it his platform.”

As for cabinet size, it has swollen to 18 ministers, up 29 per cent from the 14 ministers sworn in when Williams first took office in 2003. That's a pretty big cabinet and it's as large as the previous cabinets which Williams rightly excoriated for being huge and bloated.

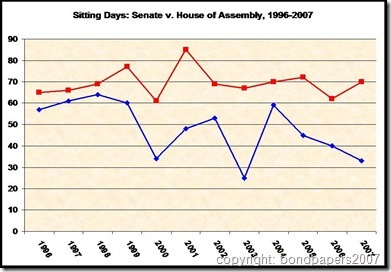

As for cabinet size, it has swollen to 18 ministers, up 29 per cent from the 14 ministers sworn in when Williams first took office in 2003. That's a pretty big cabinet and it's as large as the previous cabinets which Williams rightly excoriated for being huge and bloated. Even Tom Rideout, government's defender-in-chief on the issue of House opening delay, once promised a budget and throne speech within two weeks of his winning the leadership. Meanwhile, even the City of St. John's will have met for more days in 2007 than the House of Assembly. So will have the useless and do-nothing Senate of Canada

Even Tom Rideout, government's defender-in-chief on the issue of House opening delay, once promised a budget and throne speech within two weeks of his winning the leadership. Meanwhile, even the City of St. John's will have met for more days in 2007 than the House of Assembly. So will have the useless and do-nothing Senate of Canada What do we have to look forward to? I suspect more defensiveness (as if that were possible), more crowing over past glories like the Atlantic Accord $2billion instead of announcing new initiatives, endless rehashing of old initiatives, creative hyping of minor tinkers to existing programs and generally a whole lot less energy and ideas.

What do we have to look forward to? I suspect more defensiveness (as if that were possible), more crowing over past glories like the Atlantic Accord $2billion instead of announcing new initiatives, endless rehashing of old initiatives, creative hyping of minor tinkers to existing programs and generally a whole lot less energy and ideas.